Handle with Care

What does it take to become an occupational therapist?

Posted on June 23, 2016

Through 75 years of change, Mount Mary’s Occupational Therapists continue to treat the patient and the person.

In 1941, when Mount Mary was considering whether to establish this discipline, the president of the college, Dr. Edward Fitzpatrick, queried registered occupational therapists around the U.S. working in this newly emerging field.

The responses came in from 12 different states. They indicated the personality traits necessary for this type of work – initiative, poise, patience, cheerfulness, sympathetic understanding and a sense of humor – “leading Dr. Fitzpatrick to surmise that perhaps only saints could be therapists,” according to an early account of the department’s history written by Peg Mirenda, ’47, who served as program director from 1971 to 1987.

Throughout its 75-year history, Mount Mary’s program has proven as flexible as those ideal practitioners, molding itself to serve the shifting needs of the times. For this story, three alumnae – Laura Collins, Ann Becker and Ann Tesmer – are profiled to exemplify the dynamic spirit of the OT community.

“Occupational Therapy morphs into what the needs are,” said Jane Olson, ’82, who served as the program director from 1997 to 2009 and now directs the graduate program. “We teach not just the knowledge, but how to live it out in a way that makes a difference.”

Serving the needs of a changing world

In the early part of the 20th century, OT emerged as a practice of the Arts and Crafts movement, a social philosophy that recognized the connection between well-being and handcraft. Some of Mount Mary’s earliest workshops involved metalsmithing, woodworking and weaving – purpose-driven activities that served as pathways for war veterans with missing limbs, for example, to heal and ultimately become re-integrated into the workplace.

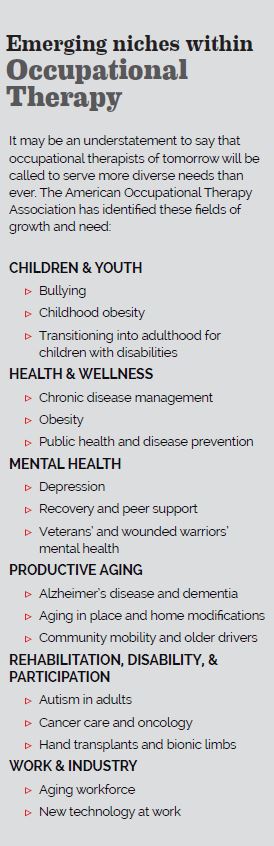

Before long the definition of meaningful activity expanded to encompass every aspect of independent living. Today occupational therapists work in hospitals, nursing facilities, home health care, schools, outpatient clinics, mental health clinics, community health clinics and more.

As the world changes, health needs expand and technology advances, this need-driven profession continues to be challenged by the same question Mount Mary leaders raised 75 years ago. And that is to look around and ask: What can a Mount Mary OT do to make the world a better place?

Ann Becker: Working with children and families

From the very first minute she enrolled in Mount Mary’s occupational therapy program, Ann (Bartosz) Becker, ’89, knew she wanted to work with children because she understood the power of early intervention. Today, as the vice president of programs for Penfield Children’s Center, Ann still marvels at how an occupational therapist can change the world.

From the very first minute she enrolled in Mount Mary’s occupational therapy program, Ann (Bartosz) Becker, ’89, knew she wanted to work with children because she understood the power of early intervention. Today, as the vice president of programs for Penfield Children’s Center, Ann still marvels at how an occupational therapist can change the world.

She remembers watching a therapy team working with an infant and, after closely assessing the child’s muscle tone, coordination, eye contact and sensory skills, recommending therapy before an official diagnosis.

“Early on, my team recognized red flags which indicated ongoing, long-term neurological problems, abnormal muscle tone and overall delays in development for this girl,” she said. “Because they recognized the abnormal development signs, the girl was able to receive early crucial treatment to facilitate her development.”

At age 2, the girl was officially diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

Becker works closely with families of children with developmental delays and disabilities to integrate an array of therapy services and early education programming. She said her occupational therapy education helped her understand the importance of practicing on two levels: Treating the condition and treating the person. This is a mindset that helps her work with families to communicate, motivate and really listen.

While parents might not understand the importance of OT goals such as building bilateral coordination or the child’s ability to cross the midline, for example, they surely want their children to become capable of tying their shoes or writing their names. When occupational therapists listen and understand these unspoken concerns, they can transform concern into powerful motivators.

“Our job is to find out what’s meaningful to families and pinpoint how the disability is impacting their day,” she said. “We need to explain to them that we are not just working on building particular skills; we are building up the function of the skill.

Ann Becker

Vice President of Programs, Penfield Children’s Center

“OTs look holistically at the physical and mental aspects of a person; that’s helped me look at and explain the bigger picture to people,” she said.

Laura Collins: Ministering to the Medically Fragile

Laura Collins: Ministering to the Medically Fragile

When Laura Collins, ‘13, graduated from Mount Mary, she began working as an occupational therapist on the transplant unit at Froedtert Hospital – against the warnings of some colleagues.

“This unit had the reputation of being a tough place to work because of the difficult and heavy caseload,” she said. The transplant service performs liver transplants, and also double lung, kidney and pancreas transplants. Many patients awaiting liver transplants suffer from liver disease caused by alcoholic cirrhosis. Hepatic encephalopathy, a loss of brain function, is often present, due to the inability of the

liver to remove toxins from the blood.

Collins has been here three years – working with patients on everything from strengthening to safety awareness and self-care and impulse control. She finds the work rewarding, because of the support she can offer through the intense variability of waiting for a donor.

One of her patients was called nine times with a potential donor match.

“Each patient and his or her family members go through an emotional roller coaster with each admission,” Laura explained. “They experience the adrenaline rush and excitement from knowing they are being called in because this ‘may be the one,’ to the disappointment upon learning the organ wasn’t viable.

There’s so much emotion for them,” she said. On his tenth trip to the hospital, he received his new liver.

“It’s rewarding to see patients, who come here at their very sickest, to be able to walk out the door. These patients are routinely in and out of the hospital and oftentimes I am treating them pre-transplant and post-transplant, which includes the very sickest patients in the Transplant ICU.”

It’s not unusual for Collins to work with patients on strengthbuilding exercises directly at the bedside. Her work represents a trend Mount Mary faculty members have recognized, that occupational therapists are working with more medically fragile patients than ever before. The department recently installed $30,000 worth of equipment that replicates an ICU bed, to ensure that students become familiarized with such equipment and the medical environment they may one day find themselves working in.

“Our focus remains on engaging patients in activities that are meaningful, but we have to understand diagnoses and how medically complex our patients are,” Inda said. “We still focus on the people, but we cannot ignore the devices attached to them.”

Ann Tesmer: Administrator today, OT forever

Recently, Ann (Klonecki) Tesmer, ’94, was named executive director of clinical operations for Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin Community Physicians, a primary care and multispecialty group with more than 350 physicians practicing in more than 25 health centers and clinics in southeastern Wisconsin.

She transitioned out of clinical practice to health care years ago, but says she still considers herself an occupational therapist at heart.

She transitioned out of clinical practice to health care years ago, but says she still considers herself an occupational therapist at heart.

When she was a therapist specializing in hand care, she treated patients recovering from traumatic hand injuries. She knew that bringing them to wellness meant more than treating the physical injury. They needed understanding, too.

“Working toward the betterment of patients goes beyond

splinting, and treating fractures or wounds,” she said. ”I really needed to listen to my patient to realize they were also suffering from underlying fears of not being able to work or support their families,” she said.

She keeps this idea of person-centered care at heart as an administrator, writing strategic and leadership development plans and setting organizational goals. This process comes naturally to her, because it closely parallels the therapy plans she’s been writing for so many years.

Devising measureable goals, documenting progress, describing the tactics and making revisions have always been in a day’s work.

“People ask me all the time if I miss clinical care – yes I do, but serving as a leader allows me to apply the broad perspective I learned as an occupational therapist.

“There is growing acceptance within health care with the idea that we are not doing something to our clients, we are working with them to achieve their goals,” Tesmer said.

“That wisdom has always been common knowledge at Mount Mary University.”